VALVE DESEASES

VALVE DESEASESWhat Is Heart Valve Disease?

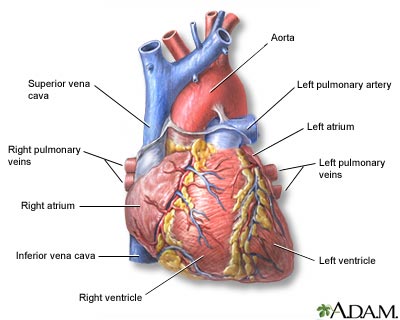

Heart valve disease is a condition in which one or more of your heart valves don't work properly. The heart has four valves: the tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid), pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary), mitral (MI-trul), and aortic (ay-OR-tik) valves.

These valves have tissue flaps that open and close with each heartbeat. The flaps make sure blood flows in the right direction through your heart's four chambers and to the rest of your body.

The illustration shows a cross-section of a healthy heart, including the four heart valves. The blue arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-poor blood flows from the body to the lungs. The red arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs to the rest of the body.

Birth defects, age-related changes, infections, or other conditions can cause one or more of your heart valves to not open fully or to let blood leak back into the heart chambers. This can make your heart work harder and affect its ability to pump blood.

Overview

How the Heart Valves Work

At the start of each heartbeat, blood returning from the body and the lungs fills the heart's two upper chambers. The mitral and tricuspid valves are located at the bottom of these chambers. As the blood builds up in the upper chambers, these valves open to allow blood to flow into the lower chambers of your heart.

After a brief delay, as the lower chambers begin to contract, the mitral and tricuspid valves shut tightly. This stops blood from flowing backward.

As the lower chambers contract, they pump blood through the pulmonary and aortic valves. The pulmonary valve opens to allow blood to flow from the right lower chamber into the pulmonary artery. This artery carries blood to the lungs to get oxygen.

At the same time, the aortic valve opens to allow blood to flow from the left lower chamber into the aorta. This aorta carries oxygen-rich blood to the body. As the contraction ends, the pulmonary and aortic valves shut tightly. This stops blood from flowing backward into the lower chambers.

For more information on how the heart pumps blood, see the animation in the "Heart Contraction and Blood Flow" section of the Diseases and Conditions Index article on How the Heart Works.

Heart Valve Problems

Heart valves can have three basic kinds of problems:

Regurgitation (re-GUR-ji-TA-shun), or backflow, occurs when a valve doesn’t close tightly. Blood leaks back into the chamber rather than flowing forward through the heart or into an artery.

In the United States, backflow is most often due to prolapse. "Prolapse" is when the flaps of the valve flop or bulge back into an upper heart chamber during a heartbeat. Prolapse mainly affects the mitral valve, but it can affect the other valves as well.

Stenosis (ste-NO-sis) occurs when the flaps of a valve thicken, stiffen, or fuse together. This prevents the heart valve from fully opening, and not enough blood flows through the valve. Some valves can have both stenosis and backflow problems.

Atresia (a-TRE-ze-AH) occurs when a heart valve lacks an opening for blood to pass through.

You can be born with heart valve disease or you can acquire it later in life. Heart valve disease that develops before birth is called a congenital (kon-JEN-i-tal) valve disease. Congenital heart valve disease can occur alone or with other congenital heart defects.

Congenital heart valve disease usually involves pulmonary or aortic valves that don't form properly. These valves may not have enough tissue flaps, they may be the wrong size or shape, or they may lack an opening through which blood can flow properly.

Acquired heart valve disease usually involves the aortic or mitral valves. Although the valve is normal at first, disease can cause problems to develop over time.

Both congenital and acquired heart valve disease can cause stenosis or backflow.

Outlook

Many people have heart valve defects or disease but don't have symptoms. For some people, the condition will stay largely the same over their lifetime and not cause any problems.

For other people, the condition will worsen slowly over time until symptoms develop. If not treated, advanced heart valve disease can cause heart failure, stroke, blood clots, or sudden death due to sudden cardiac arrest.

Currently, no medicines can cure heart valve disease. However, lifestyle changes and medicines can relieve many of the symptoms and problems linked to heart valve disease. They also can lower your risk of developing a life-threatening condition, such as stroke or sudden cardiac arrest. Eventually, you may need to have your faulty heart valve repaired or replaced.

Some types of congenital heart valve disease are so severe that the valve is repaired or replaced during infancy or childhood or even before birth. Other types may not cause problems until you're middle-aged or older, if at all.

HEART ATTACK

Figure A is an overview of the heart and coronary artery showing damage (dead heart muscle) caused by a heart attack. Figure B shows a cross-section of the coronary artery with plaque buildup and a blood clot.

A heart attack is a life-threatening event. Everyone should know the warning signs of a heart attack and how to get emergency help. Many people suffer permanent damage to their hearts or die because they do not get help immediately.

Each year, more than a million persons in the United States have a heart attack, and about half (515,000) of them die. About one-half of those who die do so within 1 hour of the start of symptoms and before reaching the hospital.

Both men and women have heart attacks.

Emergency personnel can often stop arrhythmias with emergency cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), defibrillation (electrical shock), and prompt advanced cardiac life support procedures. If care is sought soon enough, blood flow in the blocked artery can be restored in time to prevent permanent damage to the heart. Most people, however, do not seek medical care for 2 hours or more after symptoms begin. Many people wait 12 hours or longer.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

The warning signs and symptoms of a heart attack can include:

Chest discomfort. Most heart attacks involve discomfort in the center of the chest that lasts for more than a few minutes or goes away and comes back. The discomfort can feel like uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness, or pain. Heart attack pain can sometimes feel like indigestion or heartburn.

Discomfort in other areas of the upper body. Pain, discomfort, or numbness can occur in one or both arms, the back, neck, jaw, or stomach.

Shortness of breath. Difficulty in breathing often comes along with chest discomfort, but it may occur before chest discomfort.

Other symptoms. Examples include breaking out in a cold sweat, having nausea and vomiting, or feeling light-headed or dizzy.

Signs and symptoms vary from person to person. In fact, if you have a second heart attack, your symptoms may not be the same as for the first heart attack. Some people have no symptoms. This is called a "silent" heart attack.

The symptoms of angina (chest pain) can be similar to the symptoms of a heart attack. If you have angina and notice a change or a worsening of your symptoms, talk with your doctor right away.

Diagnosis of a heart attack may include the following tests:

EKG (electrocardiogram). This test is used to measure the rate and regularity of your heartbeat. A 12-lead EKG is used in diagnosing a heart attack.

Blood tests. When cells in the heart die, they release enzymes into the blood. These enzymes are called markers or biomarkers. Measuring the amount of these markers in the blood can show how much damage was done to your heart. These tests are often repeated at intervals to check for changes. The specific blood tests are:

Troponin test. This test checks the troponin levels in the blood. This blood test is considered the most accurate to see if a heart attack has occurred and how much damage it did to the heart.

CK or CK-MB test. These tests check for the amount of the different forms of creatine kinase in the blood.

Myoglobin test. This test checks for the presence of myoglobin in the blood. Myoglobin is released when the heart or other muscle is injured.

Nuclear heart scan. This test uses radioactive tracers (technetium or thallium) to outline heart chambers and major blood vessels leading to and from the heart. A nuclear heart scan shows any damage to your heart muscle.

Cardiac catheterization. A thin, flexible tube (catheter) is passed through an artery in the groin (upper thigh) or arm to reach the coronary arteries. Your doctor can use the catheter to determine pressure and blood flow in the heart's chambers, collect blood samples from the heart, and examine the arteries of the heart by x ray.

Coronary angiography. This test is usually performed along with cardiac catheterization. A dye that can be seen by using x ray is injected through the catheter into the coronary arteries. Your doctor can see the flow of blood through the heart and see where there are blockages.

Causes

Most heart attacks are caused by a blood clot that blocks one of the coronary arteries (the blood vessels that bring blood and oxygen to the heart muscle). When blood cannot reach part of your heart, that area starves for oxygen. If the blockage continues long enough, cells in the affected area die.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common underlying cause of a heart attack. CAD is the hardening and narrowing of the coronary arteries by the buildup of plaque in the inside walls (atherosclerosis). Over time, plaque buildup in the coronary arteries can:

Narrow the arteries so that less blood flows to the heart muscle

Block completely the arteries and the flow of blood

Cause blood clots to form and block the arteries

A less common cause of heart attacks is a severe spasm (tightening) of the coronary artery that cuts off blood flow to the heart. These spasms can occur in persons with or without CAD. Artery spasm can sometimes be caused by:

Taking certain drugs, such as cocaine

Emotional stress

Exposure to cold

Cigarette smoking

Reference:

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, USA.

Disclaimer

Top

Symptoms

Causes

Treatment

.svg/300px-Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped).svg.png)

An average human heart "pumps iron" by beating 100,000 times a day.

Illustration by Sharon Davis

This Valentine's Day, millions of people will exchange heart-shaped gifts of all kinds, from candy to cards. But did you know that the human heart does not actually look like the typical valentine shape?National Geographic Kids spoke with heart specialist Robert DiBianco to learn more about this important organ.According to Dr. DiBianco, the human heart is about the size of a fist."Because [the heart] is a muscle with lots of blood supplied to it, it looks red like meat," he explained. "In people who are overweight ... the heart looks yellow because it is covered with yellow fat."In the United States children are taught to place their hands over their hearts when pledging allegiance to the flag. Most people have heard that the heart is on the left side of the chest. In reality, the heart is in the middle of the chest, tucked snugly between the two lungs.But what does the heart actually do?DiBianco explained that the heart is a pump that pushes blood throughout the body. The heart moves blood by expanding and contracting (getting bigger and smaller)."Each living part of the body needs blood to live, and that's why it's important for the blood to go to different parts of the body," DiBianco said.When you're exercising, it takes your blood about ten seconds to get from your heart to your big toe and back. In fact, a kid's heart has to push blood through about 60,000 miles (96,560 kilometers) of blood vessels—that's long enough to circle the Earth two and a half times!All that pumping takes a lot of effort. To push blood, an average heart beats a hundred thousand times a day. That means that in a lifetime, the average human heart will beat more than two and a half billion times.Because the heart is so important, the American Heart Association reminds people that they need to treat their hearts with care. Exercise and healthful foods can help the heart do its job.This Valentine's Day, heart-shaped gifts will be everywhere. Maybe that's why February is also American Heart Month!

showPage(1);

var bust;

if (typeof bust == 'undefined') {

bust = Math.floor(1000000*Math.random());

}

if ((!document.images && navigator.userAgent.indexOf('Mozilla/2.') >= 0) navigator.userAgent.indexOf("WebTV")>= 0) {

document.write('');

document.write('');

} else {

document.write('');

document.write('');

document.write('');

document.write('');

}

if(cookie_is_set("userId")){ document.write(''); } else { document.write(''); }

var bust; if (typeof bust == 'undefined') { bust = Math.floor(1000000*Math.random()); } if ((!document.images && navigator.userAgent.indexOf('Mozilla/2.') >= 0) navigator.userAgent.indexOf("WebTV")>= 0) { document.write(''); document.write(''); } else { document.write(''); document.write(''); document.write(''); document.write(''); }

Activity

Pop-Up Greeting Card

Stories

The Truth Behind the Movie Meet the Robinsons

Game

Funny Fill-In: Secret Admirer!

Related Web Links

American Heart Association

© 1996-2008 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved.

Kids Home Animals Games Stories Activities Videos People & Places Photos My Page Site Map

GeoBee Challenge NG Explorer Classroom Magazine NG Kids TV NG Little Kids

Parents, Students, and Educators:nationalgeographic.com Kids Privacy Policy Contact Us National Geographic Kids Media Kit Customer Service Subscriptions Education Guide Email Newsletters Shopping Advertisers' Contests

No comments:

Post a Comment